Eleven years ago, Iceland’s premier glaciologist, Oddur Sigurðsson, declared the Okjökull, or Ok, glacier dead. Ok was once so significant that the Vikings not only named it in their ninth-century oral histories, they also wrote it down in their sagas more than two centuries later. But by the dawn of the twentieth century, the once majestic glacier had shrunk to one of Iceland’s smallest at approximately sixteen square miles wide by 165 feet deep. By 1978, Ok was down to just three square miles wide. When Sigurðsson visited in 2014, he reported the glacier was a mound of “slush” at less than fifty feet deep, no longer able to collect snowfall, build ice layers, or move itself across the land.1 In 2019, the country held a funeral for the glacier. Since then, at least four other glacier funerals have been held around the world. Iceland expects all of its 269 named glaciers, eleven percent of its total land area, to die in the next 200 years due to human-induced climate change.2

Online• Dec 15, 2025

Ohan Breiding Stages a Funeral of a Glacier

Through documentary and speculative ritual, “Belly of a Glacier,” on view at MASS MoCA, traces the slow death of Europe’s glaciers and the emotional, cultural, and environmental stakes of their disappearance.

Quick Bit by Lauren Levato Coyne

Ohan Breiding, Belly of a Glacier (To dress a wound from what shines from it) II, 2025. Giclée prints, site-specific dimensions: 11 x 22 feet overall. Photo by Jon Verney. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI.

Ohan Breiding, Belly of a Glacier (To dress a wound from what shines from it) II, 2025. Giclée prints, site-specific dimensions: 11 x 22 feet overall. Photo by Jon Verney. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI.

Ohan Breiding, Belly of a Glacier, 2024. HD video, with audio, 32:55 min. Ed of 2 + 1AP. Photo by Jon Verney. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI.

Ohan Breiding’s exhibition “Belly of a Glacier,” on view at MASS MoCA and co-organized with Williams College Museum of Art, explores what it means to lose ice through photography, drawings, and an experimental documentary. The film, also titled Belly of a Glacier, is a thirty-three-minute documentary-turned-fever-dream about the slow death of Switzerland’s Rhône Glacier. Breiding, effectively uses the documentary format to connect the physical impacts of climate change with the abstract, surreal feelings of ecological grief. The film moves through ice core drill and storage sites, lava flows, cattle grazing and giving birth, sweeping views of the Alpine landscape, the glacier melting in midday sun, and archival footage, and ends with scenes from a speculative funeral for the Rhône Glacier in the year 2050, its anticipated year of death. It also follows the residents of Obergoms, the quiet, baroque Alpine village nearest to the glacier, as they cover the ice body with five acres of thermal blankets in an attempt to insulate the ecosystem from rising temperatures. The film is compelling yet dreamy; red filters and expert editing push right up to the edge of cerebral horror.

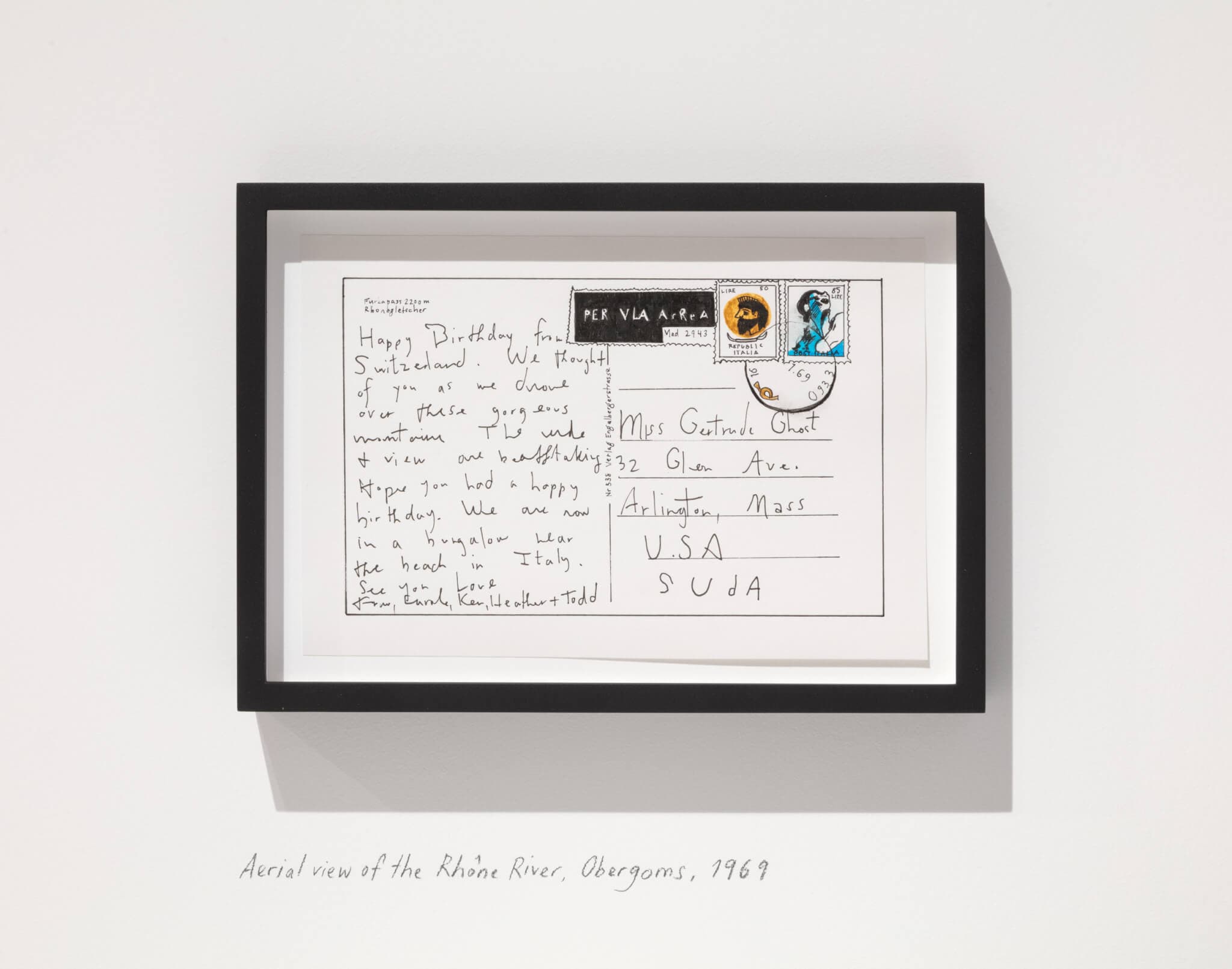

A short, narrow hall connects the exhibition’s two galleries; hanging here are seven drawings that recreate the backs of old postcards mailed from tourists visiting the Rhône Glacier, a reminder that there is more history behind the glacier than time in front of it.

Ohan Breiding, Souvenir 7 (Aerial view of the Rhône River, Obergoms 1969), 2024. Ink on paper, graphite, 4 x 6 in (drawing only). Photo by Jon Verney. Courtesy of the artist and OCHI.

In the adjacent gallery, several dozen photographs of the glacier draped in thermal blankets are installed in a large-scale collage titled Belly of a Glacier (to dress a wound from what shines from it) II (2025). Both the fabric and the glacier are shades of dirty white and pale gray. The tones of the ice supporting the hanging twists of the fabric immediately recall classical figurative marble sculptures resulting in a suggestion of Michaelangelo’s Pietà. It’s not a stretch to consider the nearly twelve-thousand-year-old glacier as a kind of mother figure to the residents of Obergoms and all the lives supported along its five-hundred-mile flow to the Mediterranean Sea. It’s also not a stretch to see the draping of veils in funerary monuments.

The artist grew up in another small village along the Rhône, playing on the ice. But not once do they dip into the treacle of nostalgia. Instead, they keep us focused on what is at stake with from-the-bones visual storytelling that is needed now, urgently.

—1 Stuart Kenny, “The Story of Okjökull—The Icelandic Glacier that Disappeared,” Much Better Adventures, November 8, 2021, https://www.muchbetteradventures.com/magazine/okjokull-glacier-history-iceland-disappeared/

—2 Jason Daley, “Plaque Memorializes First Icelandic Glacier Lost to Climate Change,” Smithsonian Magazine, July 23, 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/plaque-memorializes-first-icelandic-glacier-lost-climate-change-180972710/#:~:text=In%202014%2C%20the%20Okj%C3%B6kull%20was,its%20status%20as%20a%20glacier.

“Ohan Breiding: Belly of Glacier” is on view through January 4, 2026, at MASS MoCA,1040 MASS MoCA Way, North Adams, MA.