Archival research is fraught with more questions than answers. Objects once held by people long gone and records written in contexts of distinct social circumstances and biases rarely affirm more facts than the curiosity they incite. Of course, Boston’s historic archives are no exception. But spiraling queries must not impede the commitment to scan, study, search, and search again. They must not intimidate the sharing of our findings. Signposts for the imaginations of the next generation, no matter how elusive, might just be essential clues for uncovering the past.

“Hidden Histories” is a series of four public art projects hosted by Emerson Contemporary, in collaboration with the City of Boston’s Un-monument initiative, featuring artists Elisa Hamilton, Clareese Hill, Sue Murad, and Kameelah Janan Rasheed. As community research fellows, each artist was granted access to the Boston Athenaeum, Historic New England, and the Massachusetts Historical Society, as well as ample time for sheer exploration. Earlier this month, I spoke to Hill and Hamilton about their augmented reality works in the heart of Beacon Hill that were developed from their research. Hamilton’s project Glimpses of Glapion offers vignettes of Louis Glapion, a French West Indian–born barber and hairdresser who made a home and a career in Boston. In The Black Boston Dream Oracle, Hill unwraps the hauntology of archival objects and queries the capacity of new technologies to render them in our present moment. Hamilton and Hill’s projects can be experienced by downloading the AR platform Hoverlay on a smartphone or tablet, searching for the Un-monument channel, and heading into Beacon Hill to find the sites marked on the map provided through the application. The works are at once site-specific and augmented reality: there, but not there. For many, this presentation and the manner of accessing it will mark a unique and unfamiliar encounter with art. With patience and an appetite for exploration, visitors will trek through Beacon Hill to unveil its Black histories and understand the neighborhood anew.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Alisa Prince: With “Hidden Histories,” the two of you take on such vast histories! The Un-monument commission provided access to a breadth of resources in the Boston area. What was your approach to archives in Boston? Did you have historical figures in mind when you dove in?

Clareese Hill: No, I did not have figures in mind when we were asked to take this project on. I was approached because I am an artistic researcher. I mostly do practice-based research. So what that means is the research is the thing. The artwork is just the outcome of the question. With my project, I was interested in how the archive can become a portal. Thinking with various theorists, what does it mean to engage with an archive that’s fragmented? We don’t have clear narratives. What does it mean to speculate and fabulate around these narratives?

I wrote an article in 2024 where I was thinking about how to remap reality by disrupting Cartesian coordinates in the spatial computing landscape. How can we overlap that with reality? That’s what got me interested in working with the archives and working with archival objects. They become this moment of creating that overlap because they’re historical, but they’re suspended in their own reality being in an archive: they’re not readily available. You have to know that they’re there and how to access them. This collapses the distance between the person who would receive the archival object and find it a representation of themselves versus where the archive is and where the archival object happens to be.

I found Chloe Russell’s Dream Book from the early 1800s, maybe even late 1700s, at the Boston Athenaeum. In my project, The Black Boston Dream Oracle, each oracle is a response to the archival objects and how to speculate and create these moments of repair in the archive. Not necessarily repair in terms of trying to erase what happened or right a wrong, but a repair in who’s receiving the object versus where the object is—you know, who would find the Dream Book amazing? The Black women in Dorchester. My family is from the Caribbean, and a lot of what’s in the Dream Book is like, “If you’re dreaming about fish, you’re pregnant.” My grandma used to say that all the time. There are these moments of connection through the object that transcend these wormholes and at both ends is Black feminist knowledge production.

AP: Artifacts distanced spatially and temporarily from their original audience and how, at times, they end up seemingly distant in archives is always on my mind. Elisa, what was your method for exploring the archives?

Elisa Hamilton: I didn’t have a figure in mind early on, but at the very beginning I did start to define what that research looked like and what I was seeking. Leonie and Shana, who curated “Hidden Histories,” were so generous with us because what they did is they chose the artists; they didn’t choose the work. For an artist to have the opportunity to just dig into the archives, to be moved by the archives, to kind of stumble around and follow the breadcrumbs to these extraordinary discoveries was such a huge opportunity that artists often don’t have. And then to have the work come out of that exploration was just pretty amazing.

Early on I did choose Louis Glapion to focus on. Shana had pointed him out to me. Louis actually helped build the two-family George Middleton House, which is the second stop on the Black Heritage Trail. And if you look at the information on the house, it speaks a lot about George Middleton, but not a lot about Louis Glapion. I was really interested in learning more about Louis. I was just really captivated by his story, which was a lesser known story in the archives.

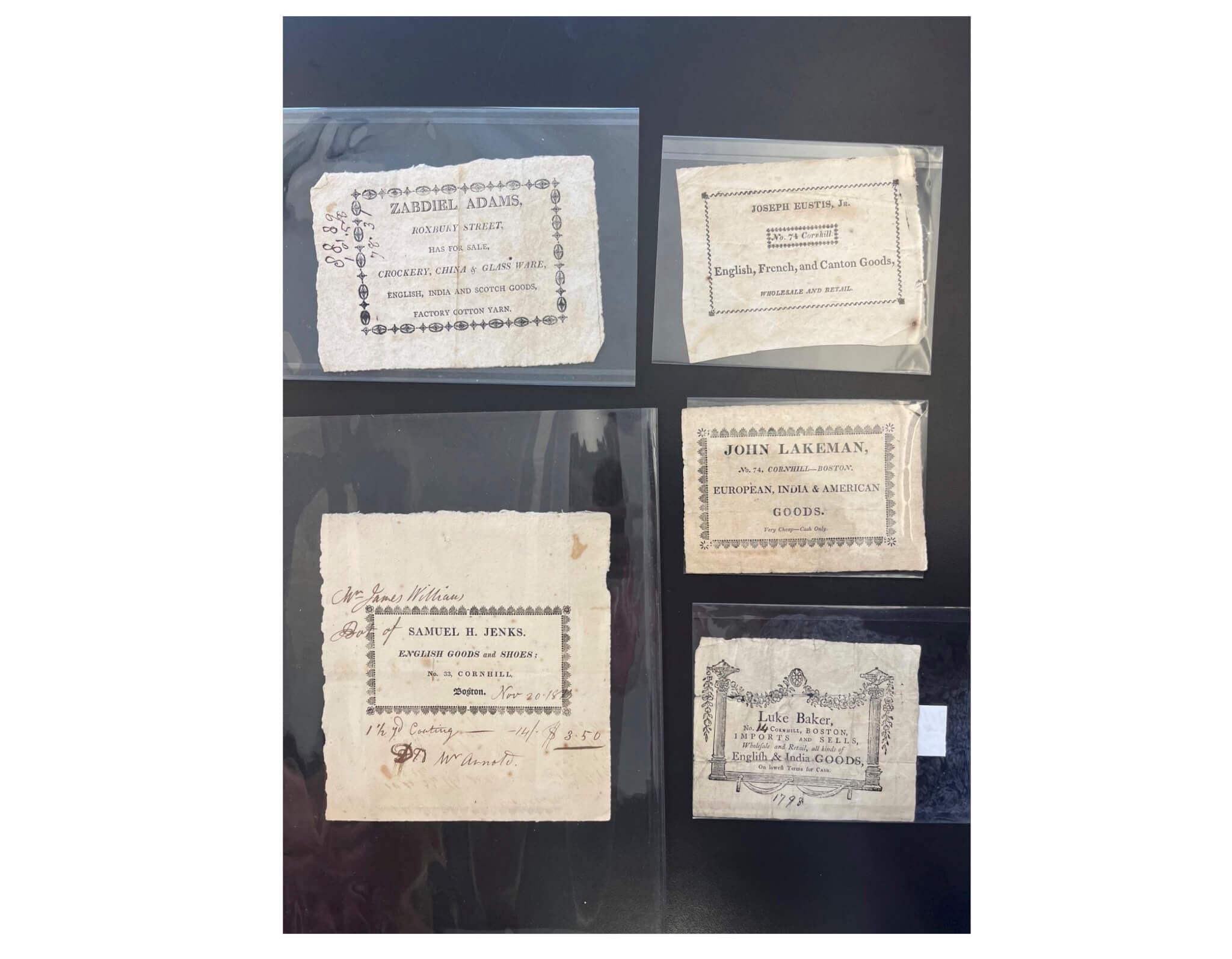

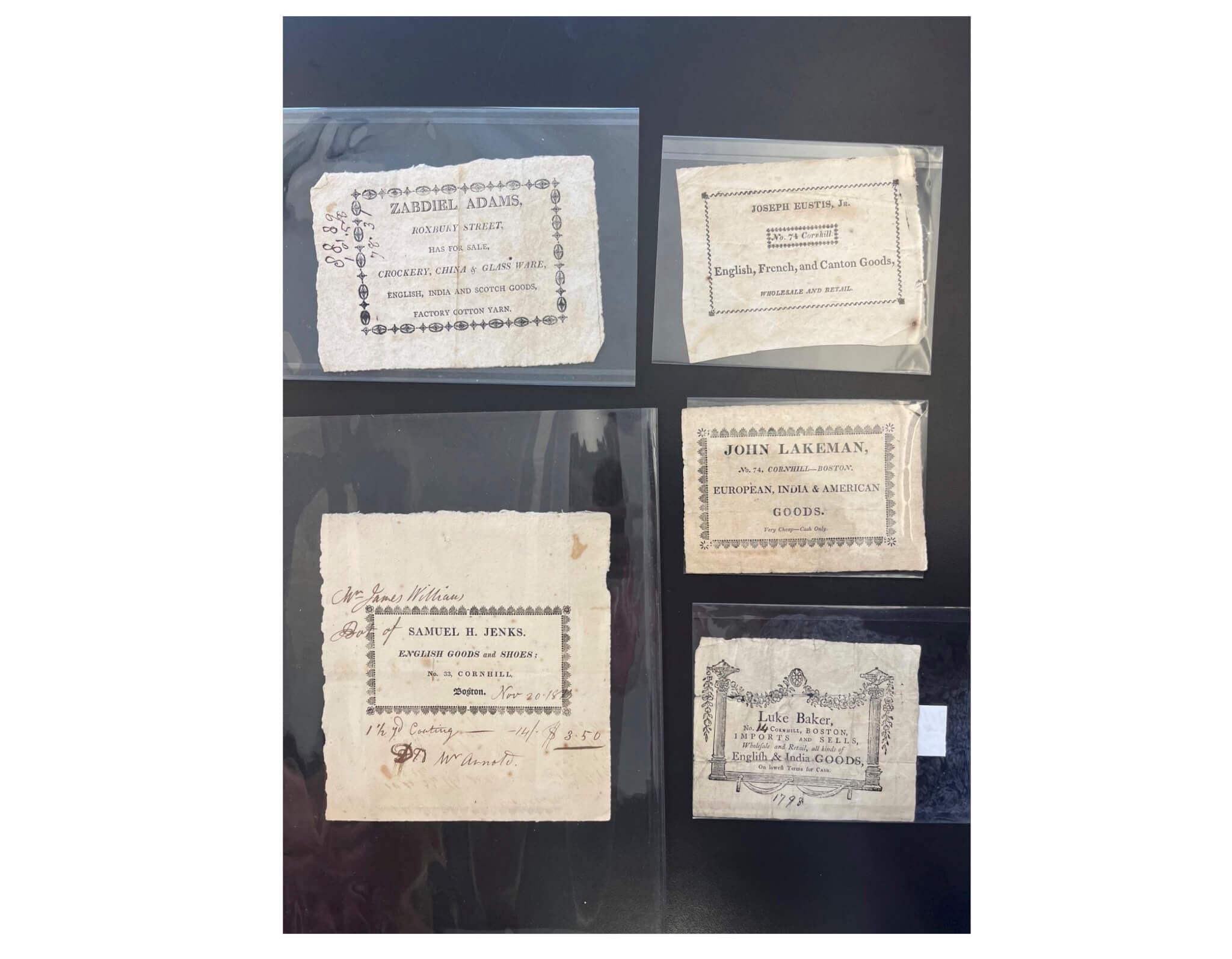

I found myself digging into a lot of newspaper archives obsessively—and newspapers for me definitely offered many of those “aha” moments. I found these advertisements that he placed in 1777. I found his death announcement calling him “an honest, honorable man of color” in the Boston Gazette. Historic New England was really informative for my work because once the project started to define itself a little more, I knew that I wanted to create what might’ve been Louis’s trade card, which is an old-fashioned business card. I really wanted it to be informed by the trade cards of that time from Boston.

Archival trade cards in the collection of Historic New England provided inspiration for Elisa Hamilton’s project Glimpses of Glapion.

AP: Glimpses of Glapion and The Black Boston Dream Oracle are works of augmented reality—what exactly do these new “realities” contain?

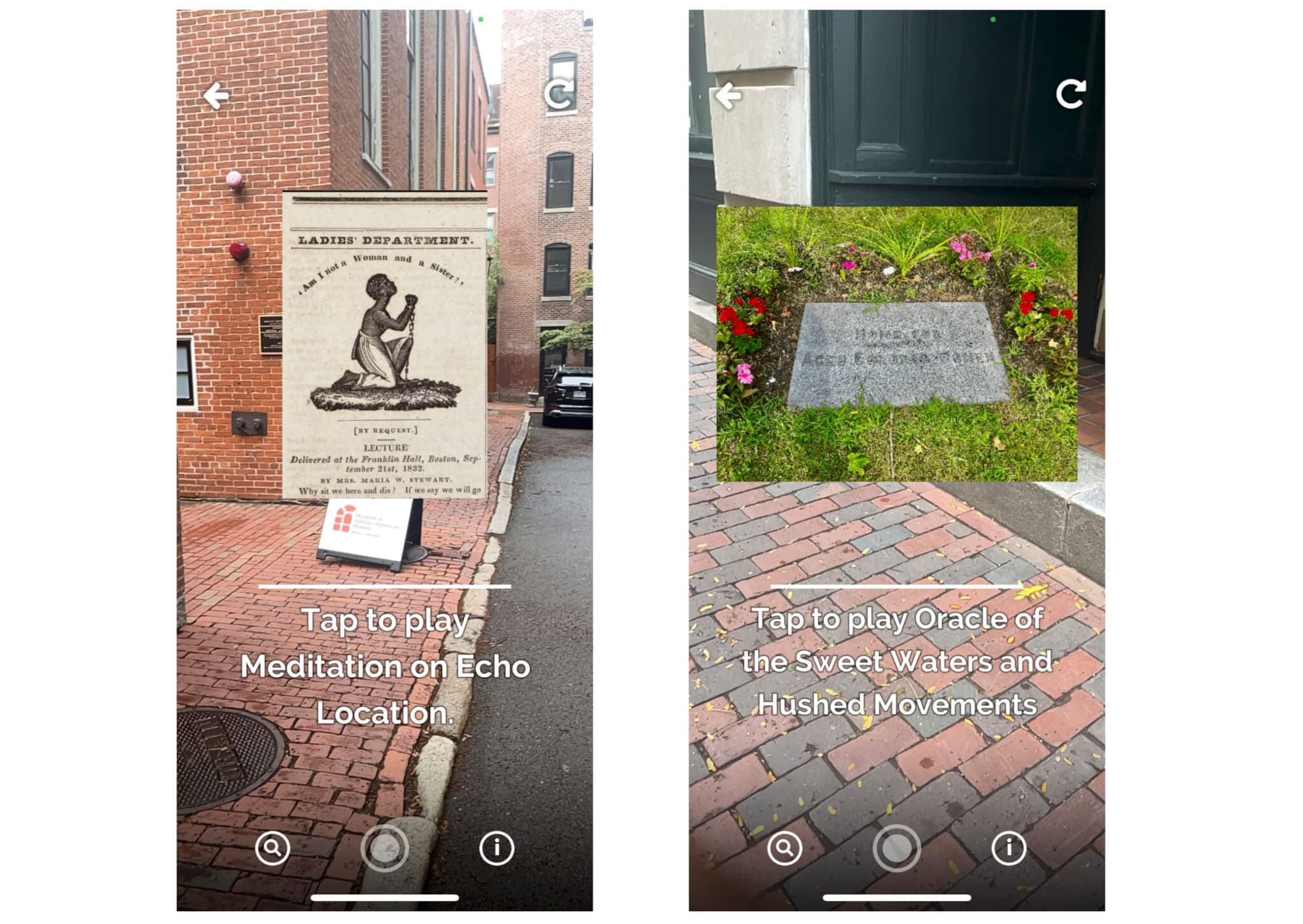

EH: This is my first augmented reality piece. My introduction to augmented reality was in 2022, through Emerson Contemporary and the City of Boston, when they provided workshops for a cohort of BIPOC folks so that we could dip our toes into AR and learn the basics of how to create an AR work. And so that’s what gave me the confidence to try this. It’s very new to me. But the site specificity of this project felt really important. And so, it’s got to be AR because this is a wicked residential neighborhood and it needs to be here without being here.

In my search to find Louis Glapion, I really was just able to gain glimpses of him. It’s four scenes: The first scene is the exposition. It introduces Louis, the location and its importance, and kind of brings people into that place, which was his home and his business in the later part of his life. Scene two introduces the viewer to his tools, his razor, his comb that he might have used, his shaving brush. Scene three introduces folks into the parlor where they can view the ladies’ hair pieces of the time that he may have created and probably took great pride in creating. Then scene four is participatory, where folks can actually try the hairstyles on each other.

AP: It is reminiscent of Snapchat, like those filters that can project into your reality. In scene two, were those actual archival objects that belonged to Glapion?

EH: No, but they are archival objects. They’re part of my archive now, because I searched intensely on eBay to find these objects that he might have used and was very fortunate. I do feel pretty strongly that they are from the 1800s. With the exception of the horn comb, which I know is a reproduction, they are real objects that were used by a barber around that time—not Louis, but you can feel the resonance and the wear and tear of them.

Hoverlay view of Elisa Hamilton’s Glimpses of Glapion, part of Emerson Contemporary’s “Hidden Histories” exhibition, 2025.

AP: It’s so intriguing how some historical objects end up in institutional archives and others are available on eBay.

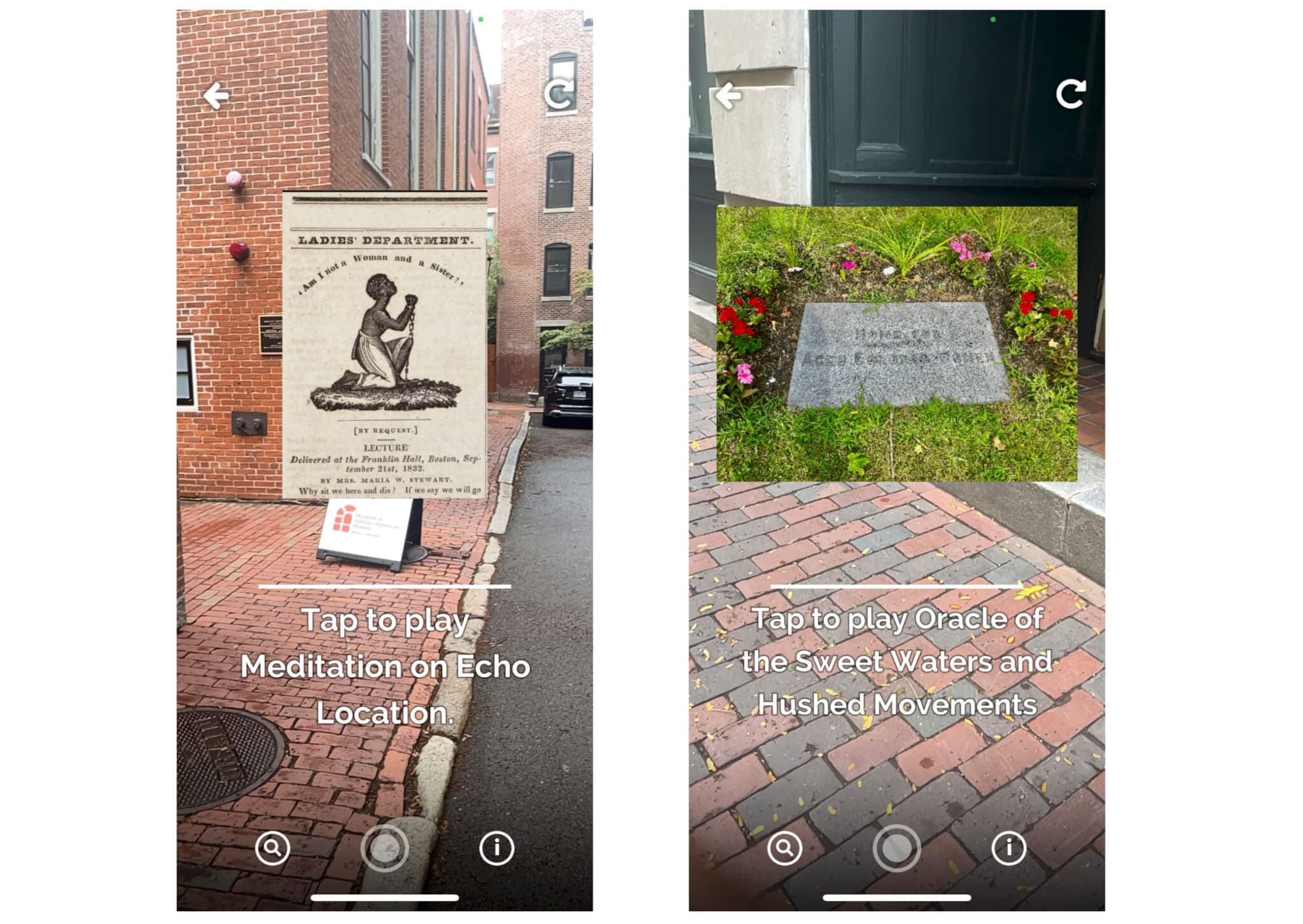

CH: I’m very fascinated with objects and their hauntology—space, objects, and the energies that they bring with them into the contemporary that may be manifested in their original operation. The Black Boston Dream Oracle is a series of five oracles. They don’t all have to be experienced. Each oracle is inspired by my journey over the last year of exploring what is in the archive. I was inspired by the Chloe Russell Dream Book (which may or may not have been actually written by her) and the archetype or stereotype of the Black female mystic, how she instrumentalized her own identity. I started to think about what it means to wage identity, because she was a real person and she did own a property in Boston right there on Joy Street, right across from where Maria Stewart lived. I just continued to go down that rabbit hole and think about how people would’ve navigated the terrain. The thing with “Hidden Histories,” and why it’s kind of a distributed exhibition—instead of an exhibition that’s nicely placed and framed—is because it is about these fragments and these pieces. And how you navigate to find these pieces is through mobility. You walk, you explore, maybe you experience part of it, you don’t experience the other part of it.

At 8 Smith Court, there are two oracles. One is inspired by Chloe Russell and the other one is inspired by Maria Stewart. With that, I chose that location because it kind of speaks to the orator, the woman of color who has a platform through the text or through the ideas. All of the oracles are narrated through an archival object. Each object is a 3D reproduction that hasn’t been edited. It’s just the object as it comes out of the technology. And so in my larger practice, I’m interested in the fidelity of these scanning devices and the failures in them, but also opacity and how Glissant points us to the opaque moments where you maybe don’t want to be fully rendered or fully legible.

AP: The two of your “Hidden Histories” projects address how Black people have shaped Boston’s landscape historically and also use Hoverlay. Is that something that you were in conversation about?

CH: Hoverlay is a Massachusetts-based company, an AR software that is web-based. So it means that you do all of your developing—you create the object in another software—and then you upload it into Hoverlay. The whole agenda for Hoverlay, if I understand it, is that it’s for artists. They want to get rid of the barriers to creating immersive media work. They’re really working with artists to kind of fill that need. Hoverlay was always super responsive, and I think it’s their way of really thinking alongside artists to create a tool that is legible and easy, but also can be disseminated easily. You do have to download the app and have to know how it works. You have to know which channel you’re going to, if you don’t have the QR code. So there are moments where you can experience dissonance because the literacy isn’t there, but their goal is to really create a tool that artists can use to create immersive works.

EH: As an artist who’s new to AR, I would say that they’re doing it pretty well. And I also want to give a shout out. I did work with a developer, Monica Storss, who’s a badass. I did the research. I had such a clear idea of what I wanted to make. It became more and more defined. But an artist needs support and a team to bring the vision to life. I want to be really open about that, too.

Hoverlay view of Clareese Hill’s The Black Boston Dream Oracle, part of Emerson Contemporary’s “Hidden Histories” exhibition, 2025.

AP: You really do feel like you’re unlocking something once you know the Hoverlay channel or find the QR code and can find these hidden histories—I mean, the title is very apt. What do you hope that audiences will take away from experiencing these works?

EH: Curiosity. Be Curious. One of the things that we all did together as an artist cohort for “Hidden Histories” with the curators, Shana and Leonie, is we went on the Black Heritage Trail. None of us had ever done it before. We couldn’t believe it. The DCR park rangers host a tour of the Black Heritage Trail pretty much every day. There’s so much here in Boston, and the Black Heritage Trail, I feel, is one of the lesser known trails here. Everybody does the Freedom Trail. I really just want to unlock curiosity. That was ultimately why I chose to make my project more accessible for folks. Of course, it’s art, it’s artful, it’s creative. But I really wanted to invite people into this media in a way that felt approachable and was an invitation to understand and to be curious about Beacon Hill, about the Black histories in Boston, about Louis Glapion, because there’s so much to know.

CH: Usually my VR pieces are more speculative and informed by philosophy, but a little bit more prescriptive in how I go about world-building these spaces. Even if you experience a fragment of one of the oracles, that’s fine, because you did have a moment to think slowly or to think with the object. I’m interested in how people, even if they don’t know they’re engaging with archival objects because it’s not made explicit in the experience, have a connection with a historic moment—an object that takes you back to the original location. It does become that moment of transporting someone back to the original kind of origin story of that location where Black people did occupy Beacon Hill. It’s hard for people to unpack that now since the demographic has shifted. But we were there.

AP: As a Black person with several generations of ancestors who lived in Boston, it’s a real treat to see artists diving into and acknowledging Boston’s Black histories. What are your relationships to the area and what led you to uncover these histories in Beacon Hill in particular?

EH: I grew up in East Arlington, grew up taking the T into Boston, and my parents were very interested in making sure that we experienced Boston. They were always finding free programs for us to go to. Some of them were weird, but they were always taking us in to see live music, taking us to the Esplanade to see the movies there. They really wanted us to feel like this city was ours. I had never experienced the Black Heritage Trail before and never really understood Beacon Hill in this way before. So I was a holder of the dominant narrative of Beacon Hill, and now I feel humbled that there was so much here that I didn’t know.

One thing that we both really held to in this work is how are we honoring these stories? We’re the artists, but this work isn’t about us. It’s about their stories. How are we as artists using this medium to uplift those stories, to share those stories? And that’s how I approach my community work. It’s always about the community. It’s never about me. I’m the creator. I have the honor of creating the work, the privilege of creating the work, but the work isn’t about me. It’s not about us. So this project has fundamentally reshaped how I understand Beacon Hill and what was there before and what could be again.

CH: I moved to Boston for my position at Northeastern, but I didn’t know anything about Beacon Hill to this level until I started doing research for the project. Upon walking around the neighborhood, it became very interesting to see that the history is kind of underground a little bit. We became translators. All these things happened in this space, but now they’re distributed; they’re suspended in different realities, but how do you translate it back into the space? We became interlocutors.The work goes where it wants to go, the narrative goes, you can’t really dictate. And Emerson was so great with that. They understood it was best to allow the research to be open-ended. Especially when you’re working with artists, it becomes this form of translation and us as interlocutors for the various moments that are maybe not in Beacon Hill. We also spent time in Haverhill. The sites called the objects back to it through us and so it kind of became a different activation.

AP: You’re catalysts for whatever the object might bring about. It’s incredible that your projects have also sparked a collaboration between the two of you. Where will your mission to reveal hidden histories take the two of you next?

EH: We got funding from the Mills Institute, which is now part of Northeastern. We’re going to be collaborating with the Museum of African American History and hosting some workshops there in the spring. We’re going to be looking at their archives and the outcomes, among other things, are going to be a collaborative mixed-reality piece that Clareese and I are creating and exhibiting someplace in the future, a publication which we’re calling an “elevated zine,” and workshops in the spring.

CH: It’s an innovation grant, and it’s really about supporting projects that seek the theme of solidarities. We pitched a proposal where it was really about thinking with the community and with the archives. We had such a great experience thinking with them during “Hidden Histories,” we would like to continue and expand that. But now we’re like, “Okay, back to being translators or being interlocutors, how do we take what we’re finding in the archives and bring it to the community?” I’m hoping this becomes an opportunity to extend what Emerson’s or the City of Boston’s original goal was with the Hoverlay workshops—to help people understand how these technologies are not novel and to also understand their full genealogy and that they’re part of the military industrial complex. They come from an extractivism economy. They’re not in the cloud and they’re not for free. They very much have a physical footprint. Which technologies you use and how ethical they are matters. We’re hoping we can have these conversations to get people to think about their role in the now. We can’t dream a future if we’re not participating in the now.

EH: We can’t shape technology if we’re not using it. This technology is here.

CH: It’s not going anywhere.

Note that while “Hidden Histories” at Emerson Contemporary officially ran through October 28, both works will remain accessible through Hoverlay beyond that date. Walking tours with the artists will take place in Spring 2026.